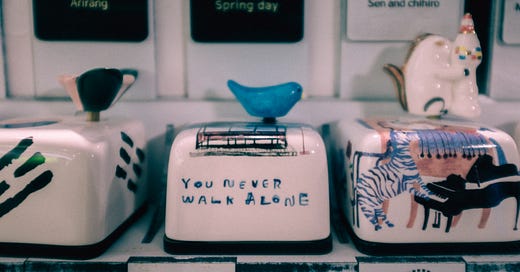

I always seem to learn new Korean words from RM of BTS.

It’s funny; I have an entire section of my newsletter dedicated to lexical gaps in English, but it’s in Korean I keep finding lacunae in my knowledge of the language. The last word Namjoon taught me was 교포, or diaspora, but this time, the word he taught me was 인연.

인연. 因緣. Inyeon. Shorthand, it means chance, or fate, or perhaps even destiny, although other words for that exist in Korean. 운명 comes to mind. Translation is an art; the Weverse1 platform translates 인연 as relationship, as in “I hope our relationship will continue,” but there are other words for that too. 관계 is another one.

There exists an idea of inter-connectedness between people in East Asia that is hard to articulate in English, especially as we in the west are so individualistic. There are ties that bind us to each other—a sense of responsibility, of accountability, or love, even between total strangers—ties that exist beyond our notion of personal relationships. The universe, or the gods, perhaps, have bound our fates together, and even in the smallest, most inconsequential interactions we can find 인연.

Perhaps this is why Korean has levels of formality in their speech. Intimacy becomes sacred in a culture where there is such importance placed on a collective, and to become intimate with others becomes a process of negotiation, assumption, permission, and trust. But the way I understand this is not through the language through which I process the world; it’s through my milk tongue, through generations of knowing that exist in my blood.

Even if I don’t speak the language as well as I ought. Or perhaps more accurately, even if I don’t speak the language as well as I think I ought.

It’s strange being a member of a diaspora, because authenticity becomes a wound I can never resolve.

Guardians of Dawn is not a series based on Korean or Chinese mythology.

Every time I come across reviews that tote Zhara as a book based on or inspired by Korean or Chinese mythology, I will admit a wince a little inside. There is no one-to-one relationship with a single country or place within the Guardians of Dawn universe and the real world, although various regions and provinces of the Morning Realms are inspired by places I have traveled and researched. To say that the series is inspired or based on any existing mythology feels false, incorrect, inauthentic, even if it is true. I adapted parts of the five-element system (wuxing) for the elemental magic of the Guardians of Dawn, played around with the Four Celestial Symbols for the girls’ animal companions (and even, a little bit the royal stars of Persian astrology), and the geography of the Morning Realms themselves is heavily drawn from the topography of East Asia. But there are no Chinese myths, no Korean myths, no Japanese myths, no stories from that part of the world contained within my books. Not really.

In the Morning Realms Dispatch section of my newsletter, I outlined a lot of things that inspired me when it came to the world of Guardians of Dawn, but I will admit to having shied away from talking about East Asia and East Asian aspects, mostly because I don’t feel as though I have permission to do so. I’m American. I was born and raised in America. We talk about cultural appropriation a lot in my circles of publishing, and I can’t help but feel the specter of, well, inappropriateness whenever it comes to discussing the elements from which I borrowed (and stole).

But the real problem isn’t permission (or lack thereof), it’s profit. Who benefits in the matter of cultural exchange and appropriation? Does one party have systemic advantages over the other? Can one party exploit the other? Is the exchange unequal in any way?

If I consider my own definition of cultural appropriation, then no, Guardians of Dawn does not qualify. Am I exploiting a marginalized community for my own gain? No. Do I have an advantage over another party that I am utilizing to get ahead? No. Do I have permission from the cultures from which I’m borrowing? Well…

I thought a lot about Western high fantasies while writing my books and why I didn’t feel the same sort of hesitation when it came to the fantastical elements of Wintersong and Shadowsong, which are inspired by Central European myths about goblins and the fae. Because I was born and raised in the west, these stories are part and parcel of the storytelling fabric of all the books I read as a child. I knew more about the goblins and the fae than I do about 도깨비 or 殭屍 or any other mythological creature from East Asia. I had heard about them my entire life, from TV, from movies, from books, from culture. I felt comfortable playing with them.

But I’m not so comfortable when it comes to playing with the artifacts of my ancestors. Perhaps it’s because the only way I can manage my ignorance is through reverence, or perhaps it’s due to the shame I’ve always felt about never quite belonging. The shame of being a “bad” Korean, a “bad” Asian-American, a “bad” member of the diaspora because I don’t know every nuance, every detail of history, every word of my mother’s homeland.

The shame of not just writing inauthentically, but being inauthentic.

You feel this shame in any number of small, myriad ways. When you mispronounce a word, when you don’t know something, when you feel like a tourist in the place where your blood and bones were forged. You also feel the judgement of all those who would nitpick any liberties or inaccuracies, even as you try to achieve a standard of perfection that you know is impossible.

There is no perfection that is too great for shame.

During a long car drive this past weekend, I had a conversation with

about why. Why we create. Why we publish. And for me, while all art comes from my fear of being lost in translation, I think I create from a place of joy. Of play. I create elaborate tableaus of make-believe; I publish for the opportunity to play, in multiple senses of the word. To make people laugh and cry, to share in the joyous delirium of creativity. It was easy to maintain that sense of play with my previous duology; it’s harder when the stakes personally feel so much larger with Guardians of Dawn. It’s hard to play when you feel the need to take yourself so seriously.So the troll in me did not.

If white authors can play with western history and mythology, why couldn’t I play with the cultural aspects of East Asia with which I was familiar? Were these not my toys as much as the Goblin King? If there is no perfection too great for shame, then I would simply not care about it altogether. I’m not writing to educate; I’m writing to entertain. Myself before anyone else. If I cannot create a world that is truly authentic to my mother’s people, then I can create a world that is truly authentic to me. And, if I’m truly honest, a world that I hope is authentic to other people in the diaspora.

All members of a diaspora are orphans of the same womb. Motherless, yet bound by the placenta of a shared blood, a red string of fate that ties us all together. That is how I choose to translate 僑胞. Orphaned and without a home but each other.

—僑胞, Nov 2022

우리의 인연이 계속 이어지기를 소망합니다,

A social media platform created by HYBE, BTS’s label’s parent company, where idols and groups can post messages and go live.