The Guardians Gazette No. 4

Appreciation, appropriation, and gatekeeping, or What we borrow, what we steal, what we pay homage to, and boundaries

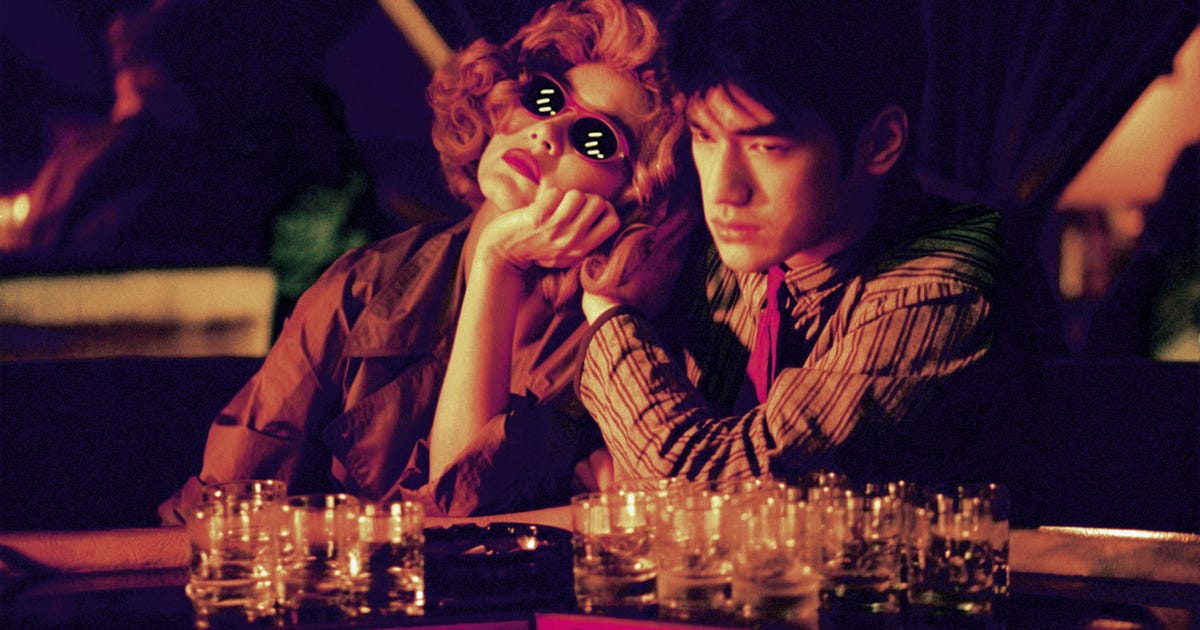

I have a weird relationship with Asian media.1

Well, weird is probably not the right word. Complicated is more correct, but doesn’t quite encompass the...awkward? uncomfortable? proud? possessive? feeling of, well, gatekeeping I want to do.

Because the minute I let the mainstream in on my secret stash of awesome, it will no longer be cool.

First things first: I am currently in the downswing of my bipolar mood cycle, so everything is harder to accomplish than it should be, including writing this essay. The thing about bipolar depression is that it’s not that I feel “sad” or “low” so much as I’m playing on Nightmare mode. It takes approximately 8000x more effort to take a goddamned shower than it should! I’m tired!

Anyway, all this to say that if this essay is less cohesive than my others have been, I apologize in advance.

So. Let’s talk about cultural appropriation.